“And in the end, it’s not the years in your life that count. It’s the life in your years.” This wisdom from Abraham Lincoln continues to inspire many lives.

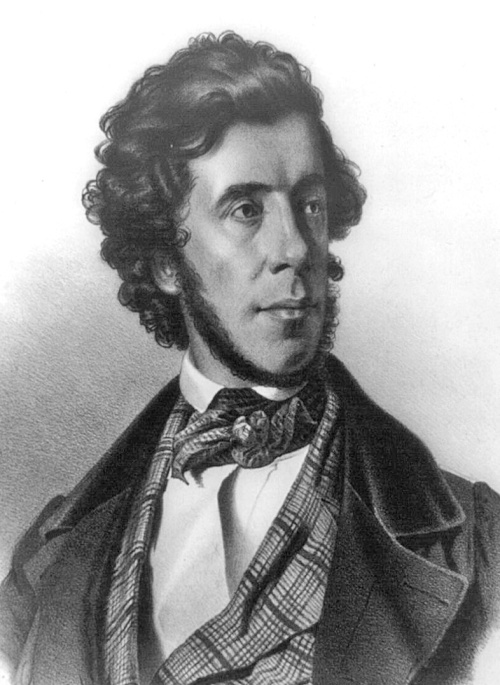

My great-grandfather, Archibald Van Orden, first saw President-Elect Lincoln at Peekskill, NY, in 1861. He would meet President Lincoln personally in 1865. Lincoln and his abiding commitment to Union would inspire Archie for a lifetime.

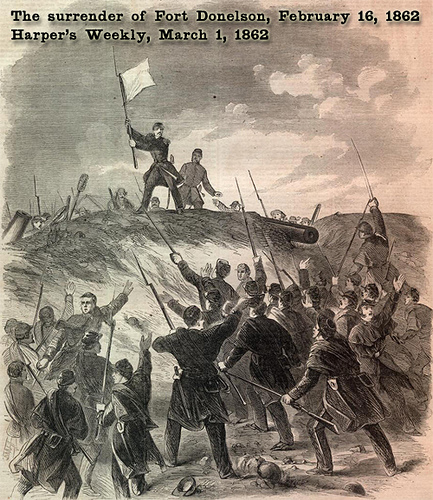

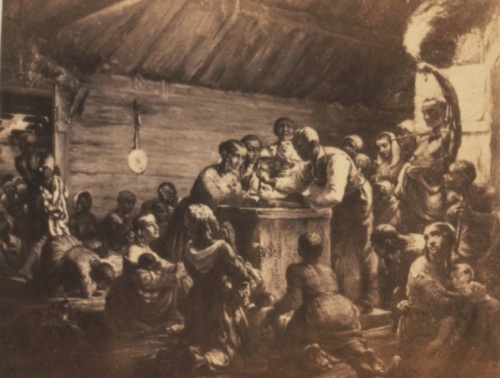

As I post in this blog highlights from the historical research I am pursuing, I am moved to add these thoughts about my great-grandfather himself: During four years serving his country in the Civil War, Archie lived more — and more fully — than most men live in a lifetime.

It is my honor and privilege to author the book that is inspired by Archie’s life — dire challenges, fearsome warfare, devastating losses, and the final triumph of love — that make his adventures more than a story of a man, and truly a tale for the ages.