By the fall of 1862, after a serious wound in his thigh from a Confederate Minié ball in the Virginia Battle of Gaines Mill, my great-grandfather Archibald Van Orden finally arrived in Washington, D.C., for recuperative care and recovery.

The recently opened Campbell Hospital in the Capitol was his first stop. Pain, sickness and infection were constant companions of Union soldiers who were able to receive care there. But the camaraderie of wounded vets encouraged all.

Like Archie, many fellow soldiers and bunk mates survived dire wounds during The Seven Days Battles. They talked of exploits in war and hopes of returning home alive.

Yet, when Archie was mustered out of the 12th NY Infantry due to his debilitating leg wound that would prevent further infantry service, he was greatly saddened. Comrades-in-arms had become his best friends and he missed them dearly.

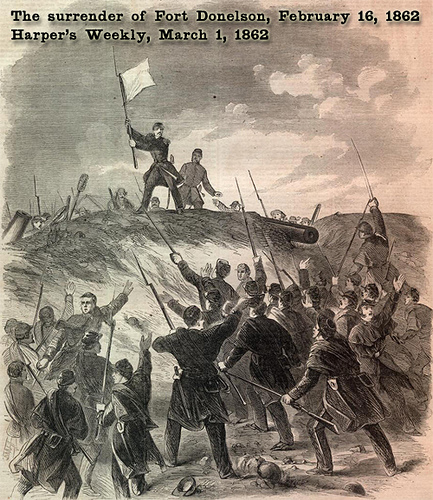

Returning home that winter to Peekskill, NY, to continue rehabilitation and recovery, Archie avidly followed reports of the war, reading newspapers and Harper’s Weekly. Distressingly, most of the news was bad for the North. Southern victories came often, and Northern losses mounted devastatingly. Emotional depression descended deeply into the psyche of Knickerbockers, who waited grudgingly for Spring to bring a new Campaign season — and victories.